edited by Eric Magrane and Christopher Cokinos

with illustrations by Paul Mirocha

University of Arizona Press, 2016

University of Arizona Press, 2016

The Sonoran Desert: A Literary Field Guide Events (& interviews and reviews)

THIS BOOK GROWS out of the Poetic Inventory of Saguaro National Park, a project that gathered eighty poets and writers to write pieces addressing species who live in Saguaro. This was held in conjunction with the 2011 BioBlitz at Saguaro National Park. All eighty of those pieces were included in a special issue of Spiral Orb. In the introduction to that issue, I wrote:

Mirroring the inventory form of the BioBlitz, in which the public joined scientists in doing species inventories within the park, the Poetic Inventory took another view at biodiversity: how do we, as Homo sapiens—one species among many—relate with other species?

This field guide includes selected work from the Poetic Inventory, as well as new pieces. It blends the form of an anthology with that of a field guide, offering both poetry and prose as well as natural history.

An except from the book

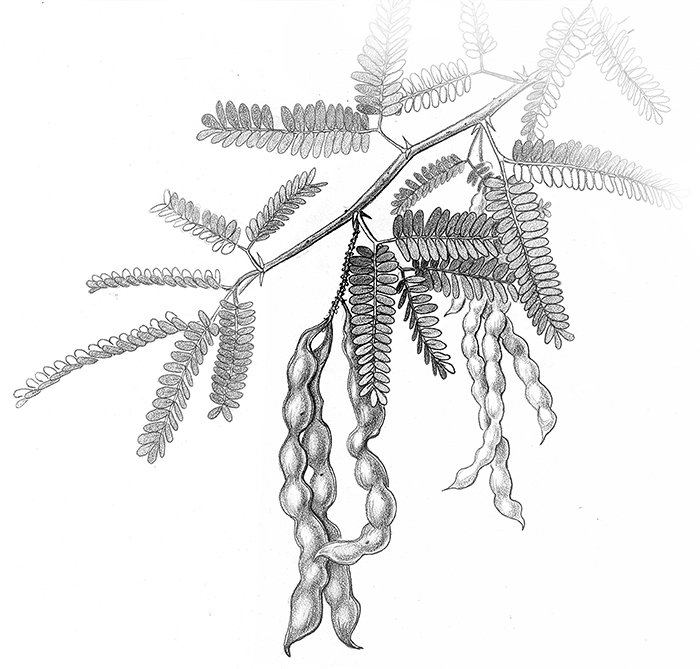

Velvet mesquite

Prosopis velutina

Eric Magrane

“The mesquite’s root system is the deepest documented; a live root was discovered in a copper mine over 160 feet (50 m) below the surface. Like all known trees, however, 90 percent of mesquite roots are in the upper 3 feet of soil, where most of the water and oxygen are concentrated. The deep roots presumably enable a mesquite to survive severe droughts, but they are not its main life support.”

– from A Natural History of the Sonoran Desert

Down here

the layers of earth

are comforting

like blankets.

The soil I think of

as time. Below the caliche

I sift through sediment

from thousands of years.

Though the sharp desert light above

is another world, its pulse

courses through me.

When the mastodons

and ground sloths roamed,

its pulse coursed through me.

When the Hohokam

in the canyon

ground my pods

in the stone

its pulse coursed through me.

When the new gatherers

of the desert

learn again how to live here,

its pulse will course through me.

And I say, I will be ready

if the drought comes.

And I say, go deep

into the Earth.

And I say, go deep

into yourself, go deep

and be ready.

~~~

Habitat: Widespread in the southwest, generally occurring below 5,000 feet elevation. The velvet mesquite prefers washes and flood plains, but is also found in drier areas. Researchers are currently studying the expansion of mesquite in grasslands habitat, which has been likely aided by cattle eating the pods and re-distributing seeds in their feces. Mesquites are often used as a native landscaping tree, as well, and provide many uses in the urban environment, especially for those practicing permaculture. Permaculture models human systems after ecological systems for sustainable living.

Description: The deciduous mesquite can grow into large trees up to 50-60 feet, but will often be smaller and shrubby in drier locations. Those who have pruned mesquite will warn you, beware its sharp thorns. With wispy leaves, an extravagent exhibition of flowers arrives in the foresummer, often attracting a congress of bees. The pods resemble flattened green beans until they turn brown in the arid foresummer, at which point you should gather them, grind them into flour, and make some pancakes. Growing interest in the desert food has even led to a cookbook produced by the group Desert Harvesters, titled Eat Mesquite!

Life History: A Natural History of the Sonoran Desert tells us that mesquite “coevolved with large herbivores, such as mastodons and ground sloths, which ate the pods and then dispersed them widely.” A tree might live individually for a couple hundred years. The tree’s taproot is the deepest known, an insurance policy for severe drought. It may also help redistribute the water from deep in the aquifer to the shrubs or young saguaros growing in its shade. It’s a relationship that Brad Lancaster, Tucson rainwater harvesting guru, calls a “mesquite guild.” This collaborative assemblage and collectivity of species makes us wonder where one organism ends and another begins.